[here's a link to Peter Rostovsky's site: www.peterrostovsky.com]

Fortunately, I was able to back right up to the freight elevator to get my work into Peter's studio building (which, by the way, appears on your right as you're avoiding potholes and swerving rigs while Manhattan-bound on the elevated BQE; "KALMAN DOLGIN" is inscribed across its brick facade.). It was far too windy to take the 40" x 60" piece out and try and walk it to the door, though it was maybe only 10 yards away. I would have parasailed right out over the Newtown Waterway in a heartbeat.

Fortunately, I was able to back right up to the freight elevator to get my work into Peter's studio building (which, by the way, appears on your right as you're avoiding potholes and swerving rigs while Manhattan-bound on the elevated BQE; "KALMAN DOLGIN" is inscribed across its brick facade.). It was far too windy to take the 40" x 60" piece out and try and walk it to the door, though it was maybe only 10 yards away. I would have parasailed right out over the Newtown Waterway in a heartbeat.

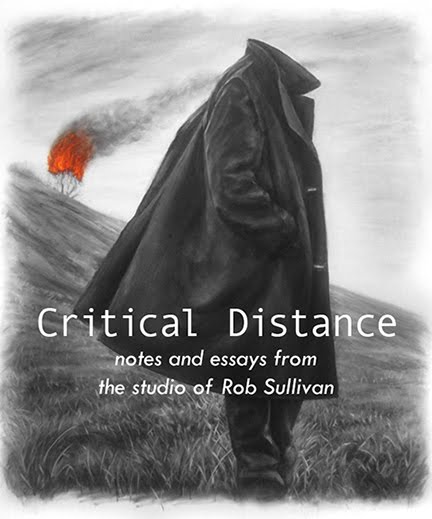

I brought what I felt was the most successful work from the program thus far: "Sublimation" (the crashed Porsche); "Atelier 2010" (the nude S.P. w/sheep); "Pteronychus" (seagulls); "All Natural" (ice cream); "Tao of Flux" (the big wave on frosted polyester); and a new work on polyester, "Catastrophe Paradox" - pictured below. [It's actually oil on polyester, as I had trouble with surface scratching on this slightly different brand of poly. Plus, the architecture proved difficult to manage in vine charcoal. I used Gamsol with Ivory Black for the monochromatic passages and full color (for fire, anyway) with Galkyd Lite for the flames.]

|

| "Catastrophe Paradox" oil on frosted polyester, 36" x 24" [Sorry for the lousy phone pic. Plus, it's still taped to the board here. Better shot forthcoming.] |

Peter got right to it, identifying his preferences and his reasons for them. Most attractive to him were the monochromatic works, the seagulls being particularly successful in his estimation. He broke it down to a very simple construct: the less number of "moves" one has to make in terms of concept/execution, the more open the work becomes. So, "Pteronychus" is one move, according to this playbook: I made a formal optical shift - that is - I merely changed the palette and tweaked the contrast. "All Natural" is two moves: an optical change plus the conflation of the two elements of sky and ice cream as an odd juxtaposition. "Sublimation" is three moves: The idealized car crash; the idealized sublime landscape; and the meshing of the two to create an open, but distinct, narrative. Now, this is not to say that the latter is an abject failure - it's more truthful to say that, the more moves one has to make, the more you can run into trouble; the "trouble" being that the work becomes too didactic. This is also not to say that a rote formula can take any image and make it a perfect painting. The image itself and its reception need to be taken into account.

I was made aware of even more representational/real painters that are engaging in this practice. Besides Peter himself, there's Michael Borremans, Eberhard Havekost, Wilhelm Sasnal, Vija Celmins, Johannes Kahrs, Anna Conway, Michael de Kok, and Cameron Martin - to name a few. Their kind of operation within the tenets of the "traditionally trained painter" is far different than what John Currin and Lisa Yuskavage do. The latter two have developed a more cynical irony about how they present their subjects, which gives them a certain leeway to paint in a more formally classical manner. It's a little negative at worst, but at best, it is a kind of game they're playing with critique. Either way, I'm less attracted to working in such a sardonic milieu. Peter is in accord, believing more in a visual/optical game with an engaged viewer rather than an expository gambit with a likely pundit.

So, then - it came to the point: what will be the underlying theme that I can get behind for the thesis work this semester? We had talked through the pros and cons of working with (and against) certain tropes and historical mechanisms in painting, especially as it pertained to my work and my engagement (critical or practiced) with those things. In as much as I enjoy the practice of "epic" painting, my visual language has not yet developed over the kind of Baroque lines necessary to pull that off. There just isn't time to experiment with that, so I will leave it as something for the future. But, what I have already done successfully is a re-presentation of the quotidian - it just needs a more streamlined visual course over a series of works. This is my plan. I have already run a number of concepts by Peter, and it became abundantly clear how some work better than others within this framework.

The board is set. The pieces are moving. We come to it at last…