|

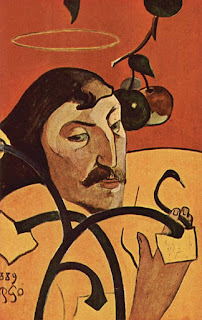

| Paul Gauguin, "Self Portrait With Halo" 1889. Oil on Wood 31" x 20" |

|

| Jean-Michel Basquiat, "Self Portrait as a Heel" 1982. Acrylic and Oil on canvas, 96" x 61.5 |

Critical Theory III

According to Henri Tajfel, "the effects of social identity are driven by a need for positive distinctiveness in which one's own group is positively distinguished from an outgroup." (519). With this in mind, we can easily hypothesize the need for the selfsame distinctiveness for an individual artist to positively distinguish themselves from other artists. There is, as noted in the theory, always a contextual/environmental factor at play. In the the case of the artist, it is the "art world": the studio; the work; the galleries; local culture; the "scene" (receptions, institutional gatherings, etc.); and the individuals involved within.

In creative fields, the want for recognition is not merely a need based upon inflation of ego - it could also be said that such a thing is beneficial for one's career. Different levels of esteem – or fame – can be achieved with different levels of acclaim. At the highest levels, it will push the artist out into the world beyond art, allowing them to be recognized by the world at large. I will discuss instances of this and the inherent problems that manifest themselves as a result. The first is an in-depth look at the life and work of Paul Gauguin. The second will bring the discussion into the contemporary with related postmodern issues of artist-as-celebrity with a focus on Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Parisian artist Paul Gauguin was highly steeped in mythologies – one path leading to a furtherance of the artist as native-bohemian (an adoption of the “noble savage” motif) – the other, to an artistic/sociopolitical movement in the discourse regarding primitive people and places. In 1879, he left behind a family and banker's job in Paris for Brittany, where he began to weave a stylized artistic fantasy. He adopted the more antiquated native tropes of Pont-Aven (wearing wooden shoes, for instance) in order to personify his artistic take on the town as an antiquated backwater. It was nothing of the kind in the 1880s; it served more of a tourist getaway for contemporary Paris. Nevertheless, this marked the beginning of Gauguin's excursion in to the promotion of two kinds of falsified “other”-ness: his own and his subjects'.

Truth be told, Gauguin's rationale for over-exoticising may be traced to his own lineage and upbringing. His mother was half-Peruvian and he spent a few of his young years in Peru. No doubt there was a part of him that sincerely desired to take his “primitive” heritage and integrate it into his art as well as his life. His work reflected an incorporation of simple, outlined and pictorially flat elements found in the older indigenous arts of island and South American cultures into his work. Critics of the time established his modern, post-Impressionist tack as “Symbolism.” An 1891 account of Gauguin by G. Albert Aurier describes this simplification through a process of depicting “multiple elements of objective reality.... [using] only lines, forms and distinctive colors that enable him to describe precisely the ideic significance of the object.” (194). This formal appropriation could be considered problematic in light of Gauguin's French colonial worldview. However, in studying the work, his adoption of this style was a highly original fusion, be it pastiche or no. His work still stands as an original paradigm shift in the formal aspects of modernist painting.

Nevertheless, his life and career in Tahiti proved to be problematic indeed. The decision to embrace his Peruvian heritage could never counter his true cultural background – that of a late 19th Century Parisian banker. This aspect is further underscored by the fact that, prior to Gauguin's arrival, French missionaries had already been hard at work in this French colonial possession for nearly a century. Gauguin's hope for an authentic native experience (much less “going native”) was an impossibility. Despite this, Gauguin applied his life and work towards the archetype of an idealized primitive civilization. His marriage to the 13 year-old Teha'amana was undoubtedly rationalized by the tradition of such youthful marriages in the culture, but it was automatically rendered problematic by his own cultural standards; French society would find such an arrangement criminal and immoral. This is further problematized by what he gained by this union, as he was in straits with regard to food and clothing, as Solomon-Godeau notes: “[B]y virtue of [Teha'amana's] well provisioned extended family, [she was] his meal ticket.” (325). It remains speculation to wonder whether it was Gauguin's inflated appetites – apropos of his “savage” persona - that kept him holding onto the fantasy of a Tahiti long past. His sources were pastiches of tales told by Teha'amana – someone who was already a generation removed from her lost culture. He depicted an incorrect and “innocent” version of this past in his paintings, promoting this misrepresentation to his collectors back in Europe.

Gauguin was indeed “a reactionary revolutionary, one who placed hope not in the modernist present and future, which he despised and feared, but in an uncorrupted, uncolonized past, a past that had, like a princely birthright, been snatched away from him, and that he ended up spending a lifetime trying to recover.” (Cotter, PC21). His career survived on the myth of the self-exiled artist. And he spent himself on maintaining it – so much so that he had to remain in exile, an embittered expatriate, finding his untimely end via complications with syphilis and alcohol abuse.

It is no wonder that the artistic evolution from the modern to the postmodern should also encompass an evolution from the “mythological” artist to the “celebrity” artist. A persona that perfectly captured the zeitgeist of the preeminent postmodern decade – the 1970s – was that of the artist Andy Warhol. With Warhol, there was no line between the artist and the work – fame was engendered by name recognition. Other artists were able to capitalize on this mania in subsequent years, parlaying their art careers into financial juggernauts, such as David Salle and Julian Schnabel. New York City was the locus point for all of this. This was the era of artist-as-superstar.

As the art market moved into highly fertile financial territory in the early 1980s, dealers and artists alike were striving for the “next big thing.” With the paradigm of the celebrity artist now in place – young bohemians flooded lower Manhattan with experimental art in hopes of hitting it big. Anything and everything was up for grabs. A young graffiti artist with the tag “SAMO” began to grab the attention of those close to the “scene.” Through a series of fortunate events, coupled with much help from his enigmatic charisma, SAMO – aka Jean-Michel Basquiat – was “discovered.”

Richard Marshall recalls that Basquiat “first became famous for his art. Then he became famous for being famous. Then he became famous for being infamous.” (15). The unfortunate circumstance of how this came to be was, in part, fueled by an unshakable drug addiction, born from the street life that Basquiat espoused at age sixteen. The other part was perhaps more insidious, and no doubt kept this sensitive young man from shaking his crippling dependency.

Similar to Gauguin, Basquiat had an ethnic background that fueled part of his artistic and intellectual makeup. He was born to Haitian parents, but in Brooklyn. Like Gauguin, he spent some childhood years in the country of his progenitors, where he learned Creole and French. Nevertheless, his native soil was very much New York. He was ultimately raised in an upper-middle-class, financially stable household, his father being an accountant. This is a problematic area that does not completely gibe with the “kid from the street” ethos that Basquiat embraced, but he understood the street life and reflected the culture back in his art with a fresh and direct style. He drew upon black historical figures and histories to reflect his Haitian-African roots and how that played into his take on street life. This was all wholly unique to the New York art scene, and he soon garnered serious attention from high-powered gallery owners and dealers.

As reviews of Basquiat's work mounted, it became noticeable that the neo-expressionist moniker was being paired with “neo-primitivist.” Much of this press hinted at an painter's intuitiveness not born from an attenuation to the culture, but rather a “savage” primitivism that smacked of heavily racial overtones. The art world of the mid 80s, despite all its liberal tendencies, did not yet know how to fully accept a young black man as its new prince, even though all the “right” people had canonized him. His misgivings over this are clear in the highly personal interview he gave to Tamra Davis in her documentary The Radiant Child. (1:03:00 – 1:04:00).

This misrepresentation of this complex and talented young artist came to its unfortunate head when Basquiat's very hero, Andy Warhol, asked him to work alongside him and produce a show together. It remains speculation to discern whether Warhol was aligning himself with this hot new upstart in order to reinvigorate a flagging career, or that he was trying to bring Jean-Michel past the last hurdle into art superstardom alongside himself, Schnabel and Salle. Unfortunately, the press read the former implication into the show, admonishing Basquiat for “playing the art world mascot.” (Reynor, 91). This had the effect of sending Basquiat into a spiral of heavy heroin use, from which he would not ever recover, dying from an overdose in 1988 at the age of 27.

It is so unfortunate and unnecessary that problems arose from the mere fact of fame being thrust upon Basquiat so quickly. In a strange reversal of the Gauguin paradigm, where the artist was the sole proprietor of the myth, and ultimately held the power of his artistic fate in hand, the impressionably naïve Basquiat was in the hands of the moneyed peoples of the art world: wealthy, powerful, white men. They sought to cash in on not just his talent, but, in a surfeit of ignorance, his “otherness.”

Works Cited:

Aurier, G. Albert. Symbolist Art Theories- a Critical Anthology. Ed. Henri Dorra. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. 192-203. Print

Cotter, Holland “The Self-Invented Artist.” New York Times. 25 Feb. 2011, New York ed. Section PC, 21. Print

Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child. Dir. Tamra Davis. Perf. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Suzanne Mallouk, Annina Nosei and Julian Schnabel. Arthouse Films, 2010. DVD.

Marshall, Richard. Jean-Michel Basquiat. New York:Whitney Museum of Art Press, 1992. Print

Reynor, Vivien. “Basquiat, Warhol.” The New York Times. 20 Sept. 1985: Arts Section, 91. Print

Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. “Going Native.” Art In America. #77 Jul. 1989. 313-329. Print

Tajfel, Henry. Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology. Eds. David O. Sears, Leonie Huddy, Robert Jervis. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. Print

No comments :

Post a Comment